A year or so ago, my Mother started using a book of old Celtic prayers. Early in the morning you can find her in our living room, and late at night in her bedroom, bent over her book. It is a book that has gained popularity among the Christian community in Britain, echoing the more explosive popularity of mindfulness – a practice that requires anchoring one’s mind in the present. In the West, this practice is hailed as new and revolutionary, people cannot believe that it has taken us so long to discover that meditative practices benefit our mental health.

The truth is, much like Columbus’s America, it is not the West’s discovery. Rather our eyes have been opened afresh to what our ancestors knew and what Egypt never forgot.

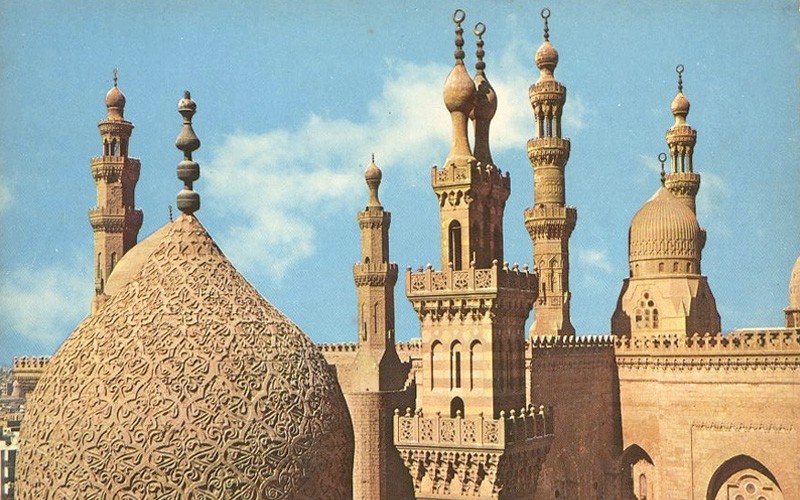

Last year, when for the first time I came to Cairo, I found something soothing in the imam’s call to prayer, even when it woke me up at 5 in the morning. On my visits to the mosques in Islamic Cairo, I marvelled at the calm community gathered together in their courtyards. Then, when on Friday the whole city paused to pray, I drove through empty streets impressed by such total rest across a city.

However, by the time I touched back down in London I was too busy bickering with my sister to recall the strange peace of those morning prayers, or of the courtyards and the silent streets. Instead I returned to a life mostly spent hectically rushing around, trying to wolf down breakfast and find my missing she simultaneously. By the time winter rolled around I had lost any appearance of sanity and all my half-hearted attempts to pray had been traded in for 5 minutes longer in bed of a morning.

Yet prayer, as it turns out, is an incredibly effective medicine. It has been scientifically proven to combat poor mental health and to reduce our stress levels, it even, supposedly, makes us nicer and improves our self-control. Perhaps this is why it is in the Arab world that I am learning to feel calm.

In my first two months living in Egypt I have clung steadfastly to this new and yet ancient prayer. Inspired by Coptic Christians I am even attempting to fast for advent, although I realised early on that I had nowhere near the amount of control that the Copts do. The steadfast faith that I have encountered amongst both Muslims and Christians in Egypt has been such a challenge to my own complacent way of thinking.

The return to community and prayer that many individuals in the West are now craving is a continuous activity here. This is evident in the architecture of the mosques in Islamic Cairo, with their large communal courtyards. It is also evident when the whole of Cairo seems to fall silent at midday on a Friday for prayer.

Yet in spite of the fact that I believe that the Middle East has helped revive these ancient practices for me, it is home that I think of as I recite the Celtic prayers. It is my mother sitting still at home in the early morning, or lying in bed late at night. It is the rural monks and nuns whose stories litter my folklore, whose words I am repeating. I think of St Patrick or St Ebba praying on gothic hillsides and feel the presence of home as I sit just off the Corniche.

But though it is my home that I think of when I pray, it is Egypt that has taught me to do so.