Cinema holds up a mirror to society and is one of the most significant tools to highlight an endangered identity and document and preserve the heritage and customs of a nation, particularly when this nation must fight for its cause. But how can they endure an endless battle yet have the ability to create? How can Palestinian filmmakers create films about their beliefs, customs, and traditions in these conditions? These heart-wrenching circumstances created a diaspora spanning from living under occupation in the West Bank, under siege in Gaza, second-class citizens in Israel, and the entire world created one of the most diverse and rich cinemas.

Here is a dive into Palestinian Cinema History:

The Beginning: 1935-1948

The first glimpses of Palestinian cinema, known as the beginning or the first period, are only archived in print. In fact, no records of these films are currently available. There is only secondary evidence, such as advertisements in newspapers. The first generation of Palestinian filmmakers mixed documentary and narrative styles. Many historians believe that Palestine launched the film industry in neighboring countries. In addition, pioneers of Palestinian cinema also worked in Egyptian and Syrian productions.

Ibrahim Hassan Sarhan produced a 20-minute documentary about Saudi Crown Prince Saud bin Abdulaziz’s visit to Palestine. It is Palestinie’s first film and dates back to 1935. Sarhan made additional films until the Nakba. He later became a refugee in Jordan and moved to the Shatila camp in Lebanon.

Epoch of Silence: 1948-1967

After the 1948 Nakba, the refugee crisis has grown in importance. Refugee camps and seeking asylum abroad became an essential component in Palestinian identity and Palestinian cinema. Palestinian filmmakers moved to neighboring countries like Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon or to non-Arab foreign countries. Consequently, they could not produce movies anymore. They left their tools and production companies at home. The political and artistic scene of these host countries influenced these filmmakers.

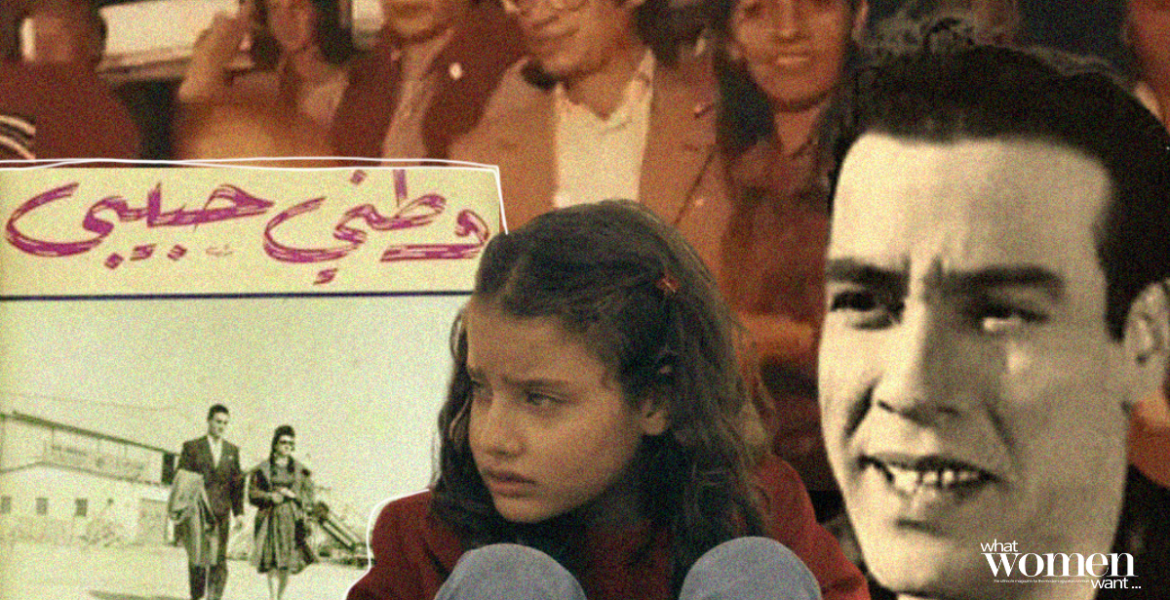

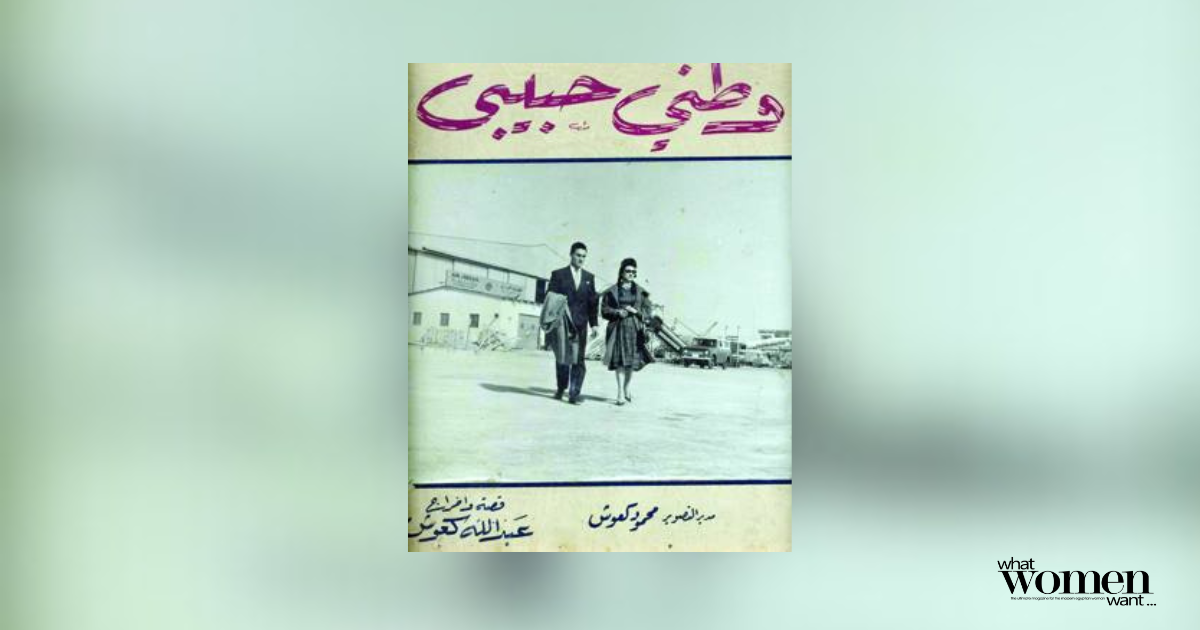

For instance, Abdallah Ka’ush directed the highly controversial Watani Habibi, produced in Jordan in 1964. It presented the Palestinian cause as a conflict between Jordan and Israel. The film was heavily criticized by film critics. In fact, film critic Hassan Abu Ghneima considered it a ‘joke.’

In 1965, the ‘Palestinian Revolution Cinema.’ was created by a group of cinematographers and directors who took it upon themselves to produce revolutionary films and rose to fame. This ended the epoch of silence.

Cinema in Exile: 1968-1982

After the Nakba, cinema was not only an art form. It was also a tool to document the struggle against the oppressor as it passed through different stages. The Palestinian political cinema movement arose alongside Palestinian resistance. Filmmakers working with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) filmed the revolution as it evolved. They documented Israeli bombings of refugee camps, the Jordanian and Lebanese civil wars, and Palestinian life under Israeli occupation. In doing so, they created a unique cinematic language that delivered their message. With the limited resources they had, they created memorable films that sustained the Palestinian political movement.

During this period, they founded the Palestine Film Unit, which produced a range of films which documented the Palestinian struggle. Some notable mentions of these films include No to a Peaceful Solution, produced by Mustafa Abu Ali, Salah Abu Hanoud, Hani Jowharieh, and Sulafa Jadallah , and 1971’s With Soul, With Blood by Mustafa Abu Ali.

The Return Home: 1983-Present

Palestinian filmography over the past decades has developed its own unique style, which marked the Fourth Period Cinema. The new wave of Palestinian directors mainly focuses on resisting the occupier and documenting an authentic Palestine. They portray Palestinians as a nation that cherishes their land and loves life. The filmmakers reflect resistance to preserving Palestinian identity and day-to-day routines, regardless of the horrific circumstances. They use their films to critique the occupation and change the Western narrative about Palestine. In addition, they have expanded their themes. They explore love and everyday life under occupation, like Farah Nablusi‘s The Present. They keep the memory of the Nakba alive, such as Darin J. Sallam’s Farha. They also explored the complex relationship between Palestinians and the Israeli security state, like in Hany Abu-Assad’s Omar.