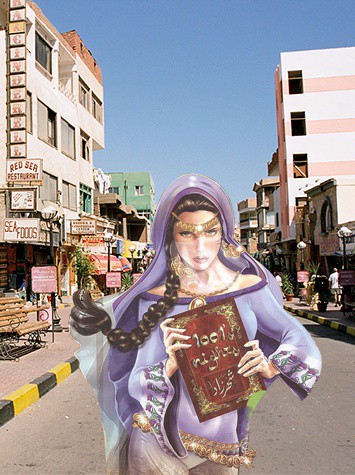

For a moment, she stands there, gazing at every word describing her life. She walks through lines that de?ne her as the world’s greatest storyteller, a wise woman, and a queen.

She listens carefully to the ?ipping of the pages that record the stories she tells yet ignore her own story. She wonders, What if I left these pages? She imagines herself naked from all the repeated words, seeing her own re?ection in a mirror and not in someone’s mind. She pictures another life, not in phrases, but in days.

She whispers to herself, “What if I’m not the storyteller, not the queen? What if I’m just a woman chasing her dreams?” Someone tells her, “You will die, the king will kill you and the one thousand and one nights will never even begin”. She hears that, and never replies.

She knows she’s been written in many ways. The original Persian narrative tells that the king, Schahrayar, marries a virgin every night, who is then destined to be killed. That was his revenge from his ?rst unfaithful wife. Then comes his Vazir’s daughter to voluntarily spend a night with him. She holds him a prisoner in a series of un?nished tales that last for One Thousand and One Nights. Out of curiosity, the king postpones her beheading. Gradually, he falls in love with her and spares her life.

Tawfeeq Elhakim wrote her into his play too, she is the beautiful queen who deranges the king with her stories. He deserts her and travels to all the places she tells him about; maybe to become a hero, or another Sindbad; maybe to understand what life is all about; and maybe because he simply doesn’t know. He travels the world, but he still can’t ?gure out her mystery. He loses interest in beauty, love, and everything, and spends the rest of his life in questions: How did she know so much? Did she go to these places? Did she meet those people, those men? Or is it all a frenzy of her imagination?

In The Nights, Sir Burton answers these questions and explains that she had perused the books, annals and legends of preceding Kings, and stories, examples, instances of bygone men and things. She had collected a thousand books of histories related to antique races and departed rulers. She had perused the works of the poets and knew them by heart. She had studied philosophy and science, arts and accomplishments. Even Korsakov wrote her into oriental melodies that painted her, sitting beside the king telling the tale of The Young Prince and Princess.

Meditating all these many and other versions that portrayed her, she sees that she is always creative, beautiful and caring, but in the end, she is an imprisoned woman. No one knows who she truly is, who she could be, or how far could she go.

Scheherazade realizes that all these stories don’t embrace her anymore. She wishes to escape every template, to run away to the desert and watch the stars so clear, to take the risk, to abandon the so called kingdom and live an adventure that she never told.

So, she moves, feeling no fear and — de?nitely — no gratefulness for the man who spared her life. He simply can’t give her something that had always been hers. This time she will not use her wisdom to trick and satisfy, but to rebel and revolutionize. Finally, she moves, she steps into a blank page, starts rewriting her own story… and breaks free.